- Geography of court fines and fees

- Debtor’s prisons

- Domestic violence cases dismissed in Tulsa County

Geography of court fines and fees

The issue of burdensome fines and fees for people involved in the justice system has received great deal of attention in recent years. Community organizations like VOICE OKC and news outlets like Oklahoma Watch brought the issue to light, writing stories and educating the public about the cycle of poverty and incarceration that excessive costs create. In 2017, Oklahoma Policy Institute released a report called The Cost Trap: How Excessive Fees Lock Oklahomans Into the Criminal Justice System without Boosting State Revenue, which examined the growth of fines and fees, the effects they have on low-income defendants, and how state collections have dwindled even as fine and fee amounts charged have grown.

For all the attention paid to the issue, however, the true extent of the problem was not clear. No one — including the courts themselves — could answer definitively how many people owed fines and fees, how much they paid, or how many people were jailed for failure to pay what they owed. Is this a problem for a few unlucky people, or does it affect a significant portion of people who become involved in the justice system?

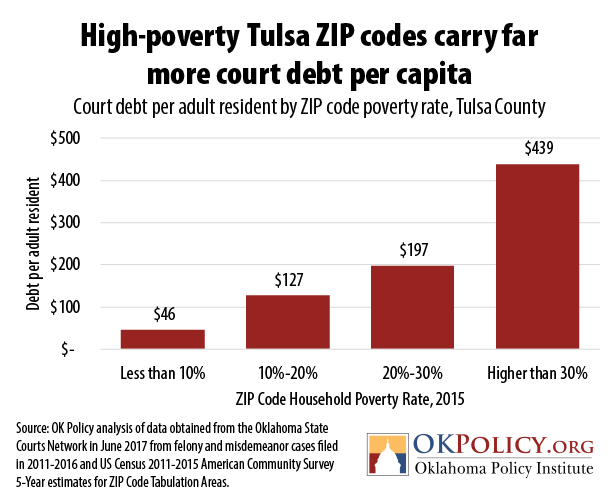

To answer those questions, we gathered thousands of case records from the Oklahoma State Court Network, which provides extensive information on the activities in 13 counties. We gathered data on how much people owe on their court costs, along with their ZIP codes, which is also publicly available. We used this data to map out where the people who owe money to the courts live and found an enormous disparity between high-poverty and low-poverty neighborhoods.

This research sheds important light on Oklahoma’s shift toward funding public services through fines and fees. It shows that people in high-poverty, heavily minority communities are being saddled with outrageous amounts of debt that they can’t pay because of their justice involvement.

This has clear implications for policy reform. Demanding that people in poverty pay millions of dollars to fund our government is a losing proposition. Courts need a way to make a realistic determination of each defendant’s ability to pay so that each person pays what they can but isn’t trapped in the justice system indefinitely. Most importantly, courts and other agencies should receive enough revenue from traditional sources like state appropriations and not rely on unreliable collections from impoverished Oklahomans for their funding.

Debtors’ prisons

Jails in Tulsa and Oklahoma Counties have struggled with overcrowding in recent years, spurring efforts to identify causes and potential solutions. One of the main drivers, according to reports published by the Vera Institute of Justice, has been a growing number of people who are arrested for failure to pay their court costs. In Tulsa, failure to pay court costs was the fourth most common offense for people booked into the county jail in 2016.

Observers from across the country have connected the rise of fines and fees with the rise in jail admissions for failure to pay, often referred to as modern-day debtor’s prisons. The jail data analyzed by the Vera Institute, however, only shows people who are booked into jail. It does not capture the people who have a warrant issued for failure to pay and are under constant threat of arrest because of it.

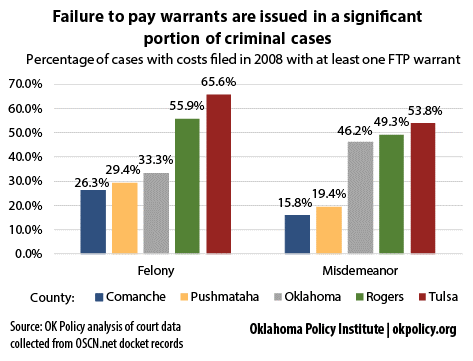

To gain a fuller understanding of the scope of the problem, we collected data from thousands of court records across five counties. The trends varied greatly from county to county, but showed that in all counties, failure to pay warrants are issued in a significant portion of cases, ranging from 16 percent of misdemeanor cases in Comanche County to 66 percent of felony cases filed in Tulsa County.

These numbers reveal a few important trends. For one, debtors’ prisons in Oklahoma are truly an epidemic, affecting a huge number of people across the state. For another, some counties are clearly more willing to incarcerate their citizens for failure to pay than others. It’s simply astounding that two in three felony convictions in Tulsa have a failure to pay warrant within 10 years.

This research shows a clear need to set more realistic expectations of what a person can pay. When defendants in two-thirds of cases can’t keep up with their payments, our courts must reassess how they approach the issue. The costs incurred by issuing warrants, arresting people who can’t pay, and keeping them in jail are enormous, and they make repayment even less likely by disrupting defendants’ lives.

Domestic violence cases dismissed in Tulsa County

Oklahoma has very high rates of domestic violence and of women killed by men. Law enforcement agencies, prosecutors, and service agencies who hope to reduce the prevalence of domestic violence face a complex web of challenges to help both survivors and perpetrators. Law enforcement agencies use a wide array of strategies to hold perpetrators accountable, often by bringing criminal charges against them, but convictions often depend on the testimony of survivors who may not want to cooperate because they fear retaliation or because they’ve reconciled with the perpetrator.

In Tulsa, a program aimed at reducing domestic violence deaths focuses on strangulation, one of the most reliable indicators that a person is at risk of being killed by their partner. The Frontier spotlighted the initiative in a recent story. The Frontier called upon data that we collected from district courts across the state to assess the effects of differing approaches to domestic violence cases.

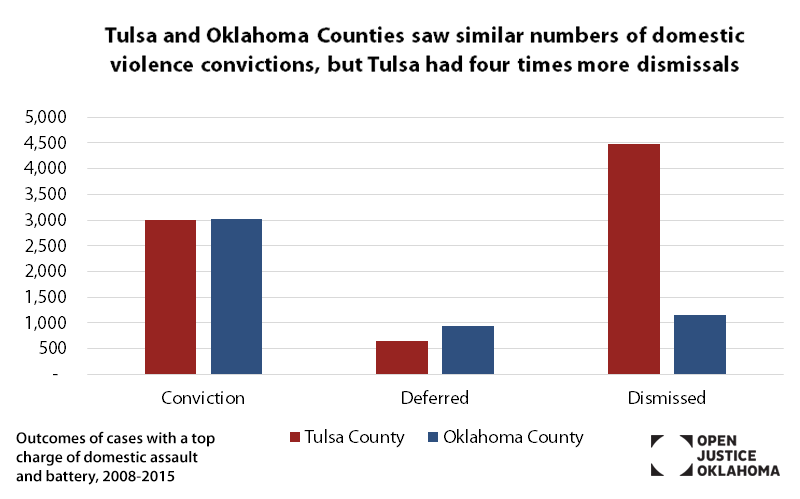

Our data showed that there were far more cases involving domestic assault and battery filed in Tulsa County compared to Oklahoma County, despite Oklahoma County having a much higher population. While the number of domestic violence convictions in the two counties was nearly identical, the number of dismissed cases was about four times higher in Tulsa County than Oklahoma County. In the Frontier story, Tulsa County Assistant District Attorney Ken Elmore said his office is more likely to file charges to allow a victim to take time to decide whether she or he wants to cooperate.

The data indicate that deciding to file so many cases results in a disproportionate number of dismissals. This is not necessarily a positive or negative trend, but it does give a better sense of the tradeoffs the strategy requires: more resources devoted to cases that will end up being dismissed and fewer resources devoted to other priorities in the District Attorney’s office.

While the data on domestic violence case outcomes may or may not spur a change in priorities within the District Attorney’s office, they do shed important light on the way resources are allocated within the offices of elected law enforcement officials.