Oklahoma’s money bail system incurs millions of dollars in fees to our most vulnerable communities and keeps thousands of our citizens incarcerated each year because they can’t afford to bond out. People accused of nonviolent offenses1 can spend weeks or months in jail, costing counties millions of dollars with no benefit to public safety.

SB 252 would ensure that people accused of misdemeanors or nonviolent felonies are considered for unsecured release and are detained only if they pose a specific threat to public safety or have a history of failing to appear for their court date.

Analysis of court data2 shows the damage our current system of money bail does to individuals and communities:

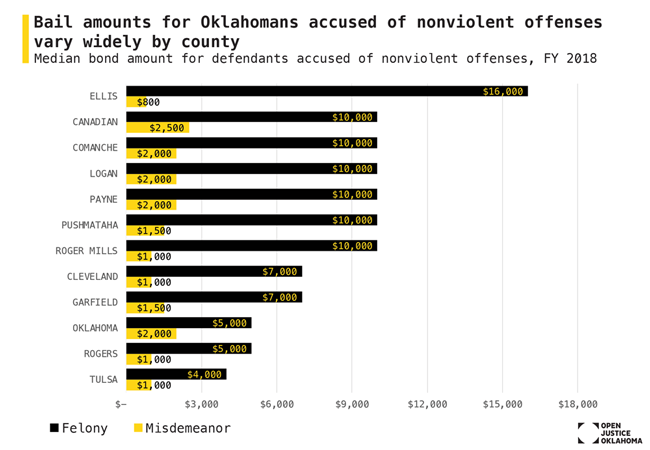

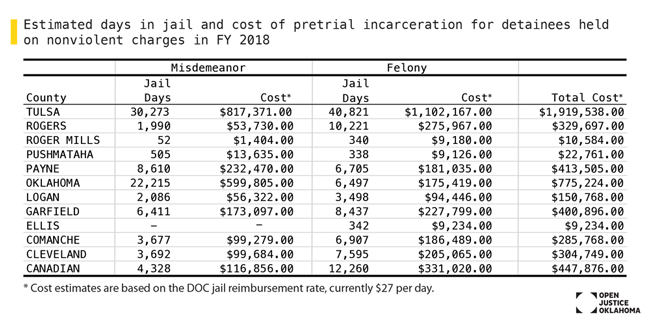

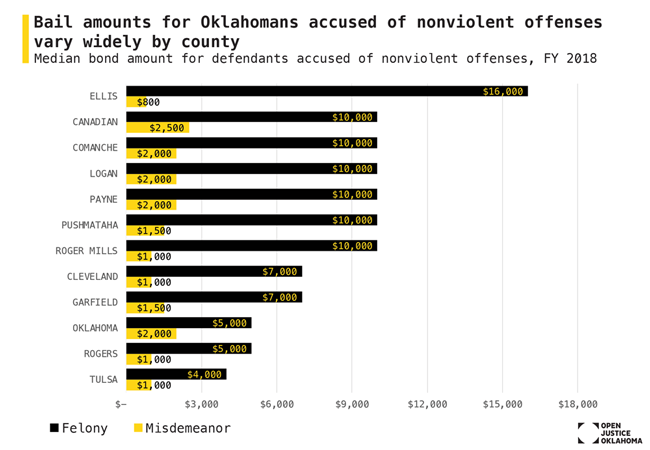

Money bail amounts vary greatly from county to county.

The median bond amount for people accused of nonviolent misdemeanors varies from a low of $800 in Ellis County to a high of $2,500 in Canadian County. The median bond amount for people accused of nonviolent felonies ranged from a low of $4,000 in Tulsa County to as high as $10,000 or more.

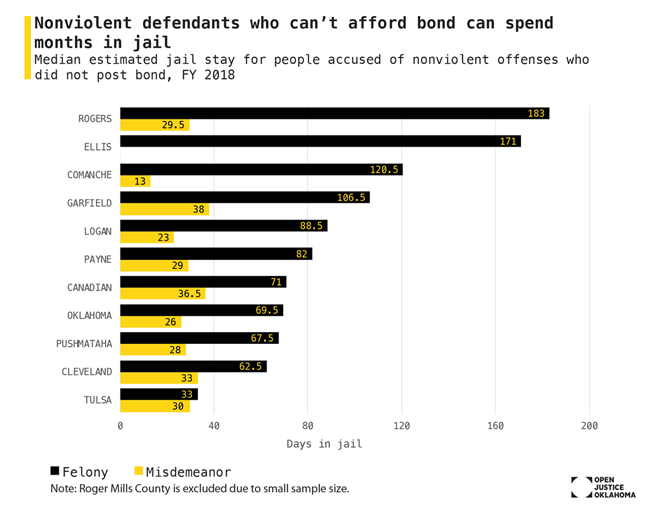

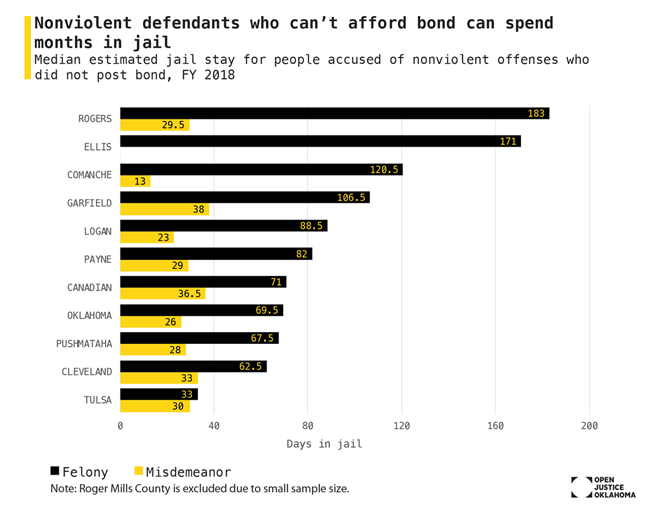

Defendants who cannot post bond spend weeks or months in jail even though they haven’t been convicted of a crime.

People accused of nonviolent misdemeanor offenses spend 2 to 6 weeks in jail before their case is resolved if they cannot afford their bond. In some counties, the average person accused of a nonviolent felony spends nearly six months in jail.

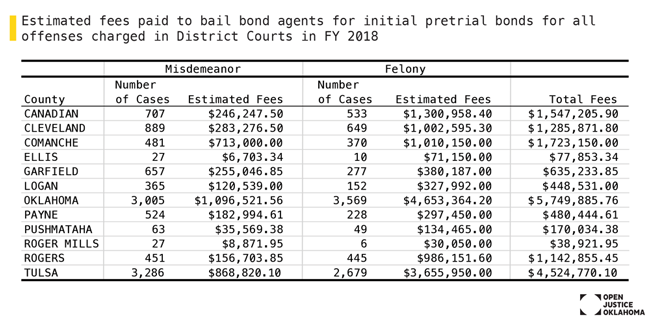

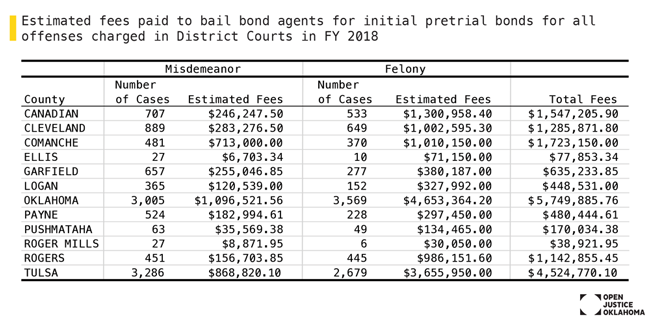

Money bail drains wealth from our most vulnerable communities.

Bail bond agents typically charge a nonrefundable fee of 10 percent to secure a person’s bond. These fees take millions of dollars from Oklahomans accused of crimes each year, even if their charges are dismissed or they are found not guilty.

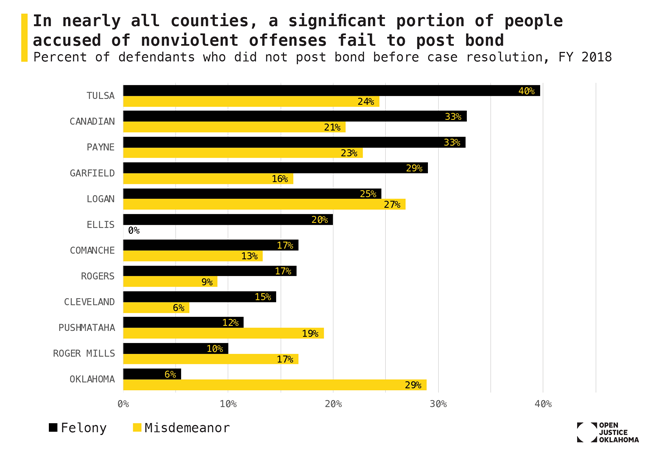

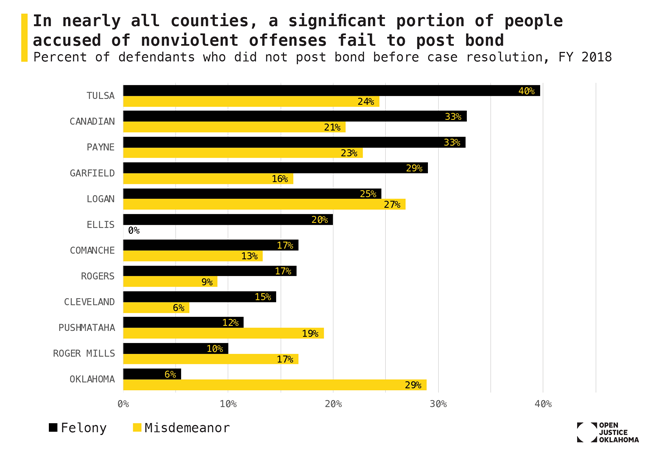

Many defendants can’t afford to bond out.

One in four nonviolent misdemeanor defendants in Pushmataha and Logan Counties remains in jail until their case is disposed. One in three people accused of nonviolent felonies in Canadian and Payne counties, and two in five defendants in Tulsa County, remain in jail until the disposition of their cases.

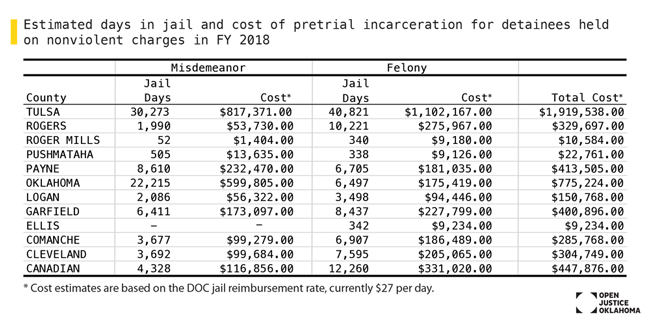

Counties could substantially reduce jail costs through smart pretrial reforms.

SB 252 would ensure that people who are accused of nonviolent offenses and are not a flight risk would be granted recognizance bonds. Many counties could realize savings of several hundred thousand dollars per year by releasing these defendants in a timely fashion without monetary conditions.

How we estimated pretrial outcomes with court data

The bail fact sheets by Open Justice Oklahoma analyze records collected from the Oklahoma State Court Network (OSCN) to estimate the impact of pretrial jail policy and practices for cases filed during Fiscal Year 2018 (July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018). We analyzed data from 12 of the 13 counties that store comprehensive court records on the Oklahoma Court Information System. Adair County was excluded because bond amounts for defendants who do not post bond are not available.

Court records for each defendant within each case were collected and analyzed to estimate the date that the defendant was booked into jail, if any, and the date that the person was released.

We used a combination of docket minute dates, offense dates, and other clues within court records to estimate a defendant’s date of booking and release from jail for their initial pretrial stay. For example, if a person was arrested, posted bond, failed to appear for a court date, was rearrested, and posted bond again; this data includes only the first arrest and bond.

Each docket entry minute was coded to infer the status of a person on the date of the minute. Classifications include: bonded out (cash, surety, or recognizance), arrested (when a warrant was returned), disposed (convicted, dismissed, or deferred), had bond set, appeared in court, was in custody, or was out of custody. The order of these dates was analyzed to identify the likely date of booking, usually the date of offense (44% of cases) or a warrant (32%). We then identified the likely date of release, most often when money bond was posted (50% of cases), a recognizance bond was issued (12.5%), or the case was disposed (16%).

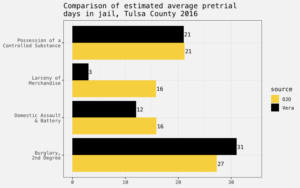

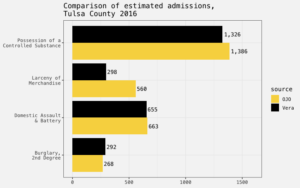

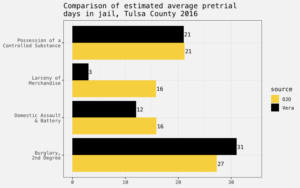

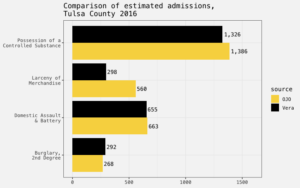

To check our results, summary data generated by this method for Tulsa County in 2016 were compared to the results of jail data analyzed by the Vera Institute. The comparison suggests that our method comes very close to data reported by Vera for most offenses, while at times over- or underestimating stays for certain offenses.

The discrepancies between the stay data generated from OSCN records by OJO and the analysis of jail data by Vera are likely due to a combination of factors:

- Differences in controlling charges: We used the first charge listed on court records as a proxy for the most serious charge, while Vera used the count with the highest bond amount.

- Incomplete or erroneous records: Data input errors mean that both jail records and court records often do not contain all the information necessary to decode the underlying factors in a case.

- Differences in charges at arrest and case filing: After a person is arrested, they are booked into jail on charges for which officers have determined there is probable cause. These are often the same as the charges a prosecutor files against a person, but prosecutors can add or drop charges based on the evidence. The difference between the charges at each step affect our ability to match trends.

Despite these considerable limitations, length of stay data generated by this method are comparable to jail data used by the Vera Institute. In the absence of better data from the facilities themselves, court records allow us to estimate the impact that bond and pretrial practices have on county and municipal governments and individuals who are accused of a crime.